As a creative talent, what role does DNA or exposure to the arts play in

your development as the sort of talent who shares his talents with

others? In the same thought, what role does a need for attention or

publicity play in your expression of your arts?

I'm sure that every factor is at play here. Genetics are undoubtedly a key ingredient, especially in the performing arts where particular physical skills and physiological traits can be required. But I think that exposure to the arts at key moments in one's development is also critical to developing an artistic mindset. Having an artist as a role model and/or being able to engage in the arts at a young age can help an individual believe in the possibility of becoming an artist. There is a leap of faith that goes with that belief, so the smaller the chasm one has to jump over, the easier it is to believe in one's ability to make the leap. In some ways, the mystique of the artist has to be shattered if one is to become an artist, so that the craft behind the art and the path to developing that craft can be understood more clearly. I think it is easier to see the potential artist in oneself once the foundations of the art are better understood; therefore, any hands-on experience and/or familiarity with the arts at an early age is very helpful to this process.

One may possess a particular talent from birth, but that talent has to be nurtured and cultivated for it to flower into anything. Perhaps that is the leveler for those of us with fewer innate abilities than others. Hard work and a dedication to the craft can overcome some genetic deficits. However, artistic inspiration and genuine creativity are other matters. Those qualities are harder to pin down. Inspiration and creativity are the parts of the art that remain the most mysterious and that cannot be reached by craft alone. One may become a respectable artist through hard work and a dedication to the craft, but no one will become a great artist without true inspiration and a deep well of creativity. That's why the mystique of great artists can never truly be shattered. Even when one studies the craft of the greats, one can't simply repeat what they've done and make great art from it. There is a unique coming together of many elements that needs to occur to make something great, and great artists have an uncanny ability to make that happen.

In terms of the need for attention or publicity, I think that is probably different for each artist. The nature of the art itself may come into play as well since some arts are more private and introspective than others. However, I believe that attention and publicity can be major motivators for some artists. I'm not sure where I stand on this myself. I'm certainly not a complete introvert, but I'm not really an extrovert, either. I enjoy performing publicly, but I don't necessarily crave it. I can say that the public aspects of my art are not as big of a deal to me as the private sphere in which the art is created. The public realm is simply something I feel I must engage with as someone who creates.

As an artist, I feel both an obligation and a compulsion to make what I do known in the ways that I can. I don't know that I can fully explain the psychological underpinnings of the artistic drive and the desire to promote one's creations to the world; however, I do know that some of this instinct is delusional - and probably necessarily so. In order to create, one has to believe that it matters. While one creates in private (which often takes a long time), one imagines the potential reception of one's work by a purely fictional audience. Though it isn't the only factor and may not even be the most important factor in creating art, this imagined audience for one's work does help to drive the creative process through to completion. Once the art is created, one feels a need to allow the actual world an opportunity to consider (or, in many cases, completely ignore) what one has created. I would feel like I've let my own art down if I didn't at least put it out there for someone to possibly take an interest in it.

In almost all cases, an artist needs to have a big enough ego to pursue the life of an artist, so big egos kind of come with the territory. I do think most artists crave some sort of public approval or favorable response to their art; most artists aren't working in complete isolation in that regard. I'm no different. I seek both affirmation and kinship. My hope is that the art I make connects with like-minded people. For better or worse, I make music for people who are like me. My target market is my own brain, and I write for an imagined audience of similarly wired people.

If

we live in a world where people most often vote thinking with their

fullness or emptied wallets, what can the future hold? In a world of

hunger, hate, wounds of war, disease, infections and more, how is one to

prioritize the arts over basic needs?

I think that the under-funding of the arts is an age-old issue in capitalist societies. It is understandable to a degree, when one views it from the point of view of the individual who is expected to choose between the arts and their own interests; however, I think that many of the choices presented to individuals in capitalist societies are false choices that are created by the system itself - and by those who have the most to gain from maintaining the status quo.

I don't think that there necessarily needs to be a choice between a person supporting the arts and that same person being able to pay their mortgage. I'm not sure that individuals should have to vote with their wallets 100% of the time in terms of the arts, but this is primarily how our society is structured.

In the United States, there are some systems of patronage for particular kinds of artistic production, but those cover a pretty narrow bandwidth of what's actually out there. Most artists - if they choose to persist as artists - are left to fend for themselves by creating their own circles of patronage.

I think it is fair to say that the majority of artists in capitalist societies choose to engage in artistic production without any promise of financial support or stability. Is this any different than other times in history? Probably not. Artistic patronage systems have never been much of an arena for the poor and working classes. In fact, we probably have more equitable programs in the arts (both public and private) right now than at most other times in history.

At the same time, though, it seems like our society doesn't currently value the arts as it might and that artistic production seems to reflect this decline in value. We've largely opted for craft over art, transaction over true inspiration or revelation, and there is a certain shallowness and redundancy in current artistic production. There is definitely more art being produced than ever, but few fields appear to be producing the kinds of great works at the rate they were produced in other eras.

Is art intended to be this transactional and functional? By this, I mean art as entertainment, art that serves a particular function, or art that is created with the explicit intent of being sold. To me, art created specifically for monetary transactions or functional purposes seems more like the definition of a trade or a handicraft.

Craft produced as a part of a trade is generally created to be functional and/or transactional, even if the product of that trade is determined at a later time to be art. Art's primary purpose really shouldn't be transactional but rather revelatory, even if artistic pieces are ultimately bought and sold. There is a lot of gray area in the middle here, but a society still needs artists creating art for art's sake for anything truly new or revelatory to emerge. However, the challenge for the artist who creates art for art's sake is to find a means to survive while remaining true to the artistic pursuit. How can artists who create art for art's sake survive without some form of patronage or public assistance?

On the other hand, there are likely too many people engaged in the arts in one form or another for the government or private foundations to pay all of them a living wage and also deal with all of the issues you've mentioned. This begs the question, should society support every person's artistic hobby or vanity project? Probably not. So what is the line between the artist and the amateur? Who gets to decide this? Should we always prioritize popularity or financial return when we consider the success of artists and their art?

In other words, should we always view art through the lens of the transaction and how successful that transaction is? Or is there another, fairer way to determine who gets supported and who doesn't? We already have foundations and arts boards doing this sort of work and public funding of the arts through grants and other programs. As artists, we might not agree with the choices made by these groups or by the market economy in the form of book publishers, art galleries, performance venues, record labels, etc., but these entities do exist and they do help to support some artists. Could all of this be done on a larger scale to support a broader variety of arts and a larger percentage of artists? I'm certain it could, but I wouldn't count on it.

I guess the bottom line is that the funding of the arts will always be secondary to the basic needs of a population even though art can play a critical role in the health and happiness of a society, especially during difficult times. I'm sure there is a middle path here, but there will always be winners and losers in the art world because society can't (or won't) support every aspiring artist. As an artist, one has to be realistic about these things and find ways to continue to produce art in spite of the many challenges to doing so. In the end, art will find a way to survive, and even thrive, in adverse circumstances, and it is the responsibility of the artist to make that happen.

It

has been said by various people that talented creators of the arts

will be recognized and sanctioned by society and financial rewards. Do

you think that is true? Or is it an accident or circumstance that

those of great talents are recognized? As a poet I am very aware that

popularity rather than quality is often more important in the process of

getting paid for your works.

The idea that talent will always be recognized has never been true. Recognition is generally due to both accident and circumstance. Those who are recognized as talented artists are just the tip the iceberg in terms of the actual talent out there in the world. In fact, there are simply too many talented people who are worthy of recognition for it to happen. Of course, no successful artist really wants to believe that, but it is true. Along the way, enough talented artists have been raised up by circumstance and luck to be in a position to create the great works that we have, but that doesn't mean that great works couldn't have been created by other people who were discouraged or prevented from creating art by their particular circumstance.

All one needs to do is look at the changing demographics of successful artistic production in the United States from the early 20th century to the early 21st century to understand the role of circumstance as it pertains to producing great artists. We also know that there are plenty of artists of marginal merit who have been widely recognized by society and who have reaped huge financial rewards. This wouldn't be possible if only talented artists and great works of art were broadly recognized and rewarded. Also, if this were true, Vincent van Gogh would have been widely celebrated as a great artist during his lifetime, yet he wasn't. Sometimes great art is out of step with the culture that produces the artist, and when art is truly innovative, there is always a risk that the public and critics won't be prepared to regard it for what it is.

For those reasons, I don't think there is a strong correlation between artistic potential and financial success. There is, however, a strong correlation between artistic competence and financial success when it is coupled with the even stronger correlation between marketable artistic creations and financial success, by which I mean that certain types of artistic productions fit into the market (and entertainment) economy better than others. Those types of creations are more likely to be rewarded than others, so if one is artistically competent and willing to create art that is already proven to be marketable, there is a stronger likelihood of financial success than for a great artist who chooses to make less marketable art.

But does marketability make the art more artistic or the artist more talented? I think we all know this is not true on the face of it, but a lack of marketability doesn't necessarily make the art any better, either. Nevertheless, if a work is going to be considered good or great, at some point, an audience or some critics are going to have to get behind it. Though it's not necessarily in the the job description of the artist, many of the most successful artists do aggressively lobby critics and engage with audiences on their own behalf in order to create a market for their work. This entrepreneurial spirit doesn't necessarily make them better artists, but it does ensure their works will be considered for possibilities that a more reticent artist's works may not.

I think the internet has exacerbated this issue of transaction-oriented art along with the changing means of production and distribution for many of the arts. It is now relatively easy for many artists to create, self-publish, and self-promote compared to 25 years ago. In some ways, the new possibilities are a boon to artists, but this ability to self-publish and self-promote has its downsides as well. One obvious downside is that artists have been encouraged to become entrepreneurs in order to succeed in the internet age. This means that they have to think of themselves and their art in terms of its marketability and not necessarily in terms of its subject matter, so this shifts the focus of the artist from the creation to brand building and brand promotion. The question is if the art itself suffers from these shifting priorities.

This is the acceleration of a trend toward the commodification of art over the past few centuries. Also, until recently, there were generally intermediaries who handled the business aspects on behalf of the artist. This was by no means a perfect system, but it did allow artists to put most of their mental energy toward the act of creation. This system allowed for more introverted and socially uncomfortable artists to succeed, because they had outgoing representatives out in the world to front for them. However, as more and more artists are expected to front for themselves, the survivors will likely be the ones who are most comfortable projecting themselves out into the world. Even artists who can afford representation are expected to present themselves as media personalities, whether they do this with proxies or on their own. These social pressures have definitely changed the nature of who can expect to succeed in the business aspects of art.

At some point you have to ask yourself, what does all of this have to do with artistic talent and artistic production? At what point are we considering the works themselves? Do we really imagine that all of the best artists are extroverts? So, this points to a structural issue with the current system that is likely impacting the development and reach of many otherwise talented artists.

Is

there a kind of government or form of economy that rewards a creative

artist? Would the sanction of being recognized as an officially state

sanctioned creative talent help, or would it cause a divide even more

about popularity and conformity over individuality and quality?

I'm not sure there is a great answer to this question. As you've pointed out, every society has its upsides and downsides in regard to its support for the arts. In monarchies, artists need to impress the monarch. In totalitarian regimes, art is used to promote state interests. In highly religious societies, art is valued when it reflects specific religious beliefs. In a true communist society, artists might be judged more by their utility to the society than their superb technique or depth of perception, etc. I'm simplifying here, of course, but I don't think it is a great idea to romanticize other societies' commitment to the arts even though many different types of societies have produced great artists and great art throughout recorded history.

In liberal democracies, there is probably more opportunity for individual expression in the arts than in many other types of societies, and there can be government and education systems to sanction and promote the arts without preconceived notions or idiosyncratic expectations. I'd imagine a liberal democracy with a balanced blend of socialist and capitalist institutions would be about the best environment for artists to flourish; however, much of the great art in history has been created by artists living in harsh, challenging environments where one wouldn't believe that art could flourish. So, hardship itself can be a determining factor in the creation of a great artist. Sometimes the artist has to pass through the crucible to become great. In some cases, affluence itself can be the artist's greatest enemy. At its best, art unpredictable and enigmatic; it finds a way to exist in spite of things.

If

the Earth is struggling in the face of global warming, ocean fishery

collapse, pandemics, war and pollution, what way could the arts help

solve the problems mentioned? Or is it that when the arts are used in

such ways it becomes propaganda, and less truly the arts? In the service

of a good or moral cause, shouldn't the arts be used thus?

I suppose it all depends on the art and the circumstance of its creation. I'm not sure there is any hard and fast rule about this. A great deal of art already seeks to reveal and/or edify, so putting it use in the service of a cause might be a natural thing in those cases; however, much of the art created for the purpose of promoting a moral or social cause has limited value when considered outside of that paradigm.

Perhaps this comes down to the quality of the artist. There are some artists who have become known through their involvement with political and social justice movements who eventually transcended those movements because their art had a more universal appeal. My guess is that this happens less often than the opposite scenario, which is artists who cannot transcend the movement that made them popular. Bob Dylan would be a good example of this; he was able to flourish even after the movement that spawned his popularity faded. On the other hand, his contemporary Phil Ochs did not have the same ability to transcend the anti-war, socialist-oriented folk music movement that they both came out of. Still, it is hard to argue that the Greenwich Village folk music scene of the 1960s didn't create some great music while opening up a few minds and raising awareness to some important topics in the process. Was all of that music actually great? Probably not. But the movement itself was important, both socially and artistically, because some great artists were a part of it.

On the flip side, social movements can also be a refuge for bad art made by artists who receive adulation for simply giving the audience exactly what they already desire, so you have to use judgment when assessing the value of the art in situations like that. As a songwriter, I tend to avoid writing topical songs; however, when I was younger, I did write several topical songs, including some anti-war, socialist-oriented folk songs during the first Gulf War in the early 1990s. Does anyone remember my classic protest song, "Supermarket War"? I didn't think so. That war only lasted about six weeks. In fact, I only performed the song for an audience once before the war that spawned it was over. From that experience, I realized that songs like this had much less relevance once the topic itself was no longer topical. I eventually came to the conclusion that while you do need to reference specific things in your writing to make it tangible and relatable, you also need to make sure that you are writing with an eye to posterity; otherwise, you run the risk of writing about things that become dated very quickly because they don't make much sense outside of a particular context.

Typically, if you keep to the story without introducing judgments, dogma, or platitudes, the story will connect itself to larger realities. A good example of a topical song that tells a story about a topical event in a compelling way that still seems relevant 40 years later is"Biko" by Peter Gabriel. Gabriel uses the song to put a spotlight on apartheid in South Africa, though he never mentions apartheid by name. Instead, he focuses the lyrics on the death of the activist Stephen Biko at the hands of the police in Port Elizabeth. The story in the lyrics and the music are both compelling and give the listener just enough to understand the situation without completely directing the listener's outrage. A great writer is able to elicit a particular emotional response without telling the reader or listener exactly what to think. And that ability is really the art; it is what makes a great artist great, and it is also why you can't generalize about the purpose of art, because great artists will defy any norms you attempt to erect around

art.

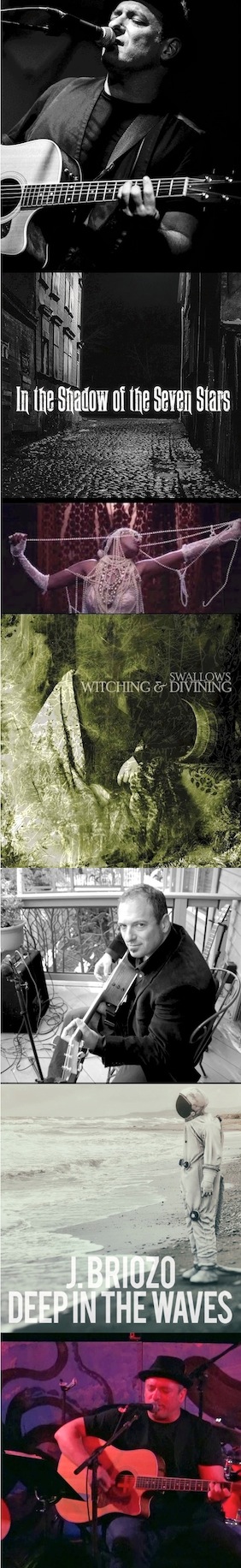

All images shown are ©copyright the respective owners

No comments:

Post a Comment